Ask The GMs: Giving Players The Power To Choose Their Own Adventures

How do you create a campaign that gives the players absolute freedom but still leaves the GM in control?

|

|

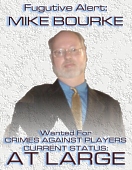

Mike’s Answer:

The good news is that it IS possible. In fact, it sounds like you are well on your way to achieving your objectives. However, it also sounds like you are well on your way to running a plot train (with limited switching points) and are concerned about it running off the rails. This would make it no more character-driven than a colouring book; but again, you seem to have escaped this particular trap fairly adroitly, letting the characters believe whatever conclusions the players have reached, regardless of whether or not that is what is actually taking place.

You should never force the players to wrap their heads around the plot – in a truly character-driven campaign, they will make mistakes and wrong assumptions, and reach faulty conclusions. But they will also learn from these.

So here’s my recipe for making your campaign truly character-diven, regardless of the amount of combat that you want to take place, based on the process that I am using in my Shards Of Divinity campaign:

Prerequisite: Active Players with Motivated Characters

The first thing to note is that none of this will work if your players are the types who need their scenarios served up to them on a plate. And the second thing to note is that it won’t work unless the PCs come pre-loaded with back stories that motivate them to be interested. A little personal stake in the outcome makes a big difference.

The key to achieving the first is something that’s eluded me for decades, so I can’t help you there, but it sounds like you’ve got that aspect of things cooking along quite nicely anyway (I’m moderately jealous, but wouldn’t trade in the players I’ve got anyway).

The key to achieving the second is to ensure that much of the character backgrounds are open-ended, unresolved, or otherwise unexplained. Even if the character thinks he knows why the Warlord slew his parents, and that the Warlord was captured and hung for his attempted revolution, and has written as much in his background, you can still place a hidden shadowy figure behind the known villain that the character knows nothing about – in which case, the revolution may have gone underground, but the wheels are still in motion, and rumours of distant events deriving from the revolutionary activities should resonate with this element of the character’s background.

Establish the big picture

The first step to achieving a truly character-driven campaign is to determine the big picture – who are the various vested interests, and who are the opposition (in general terms). Note that there will be many of these, and most of them will be side-issues to the real plot. Power brings power-struggles with it, almost by definition. It doesn’t matter what someone has, someone else will want it. Every significant power bloc should have a defined opposing power bloc, and the drive of the campaign should emerge from the tension, the move-and-countermove, between these groups. And don’t neglect the potential of groups that are being blackmailed into activities they would not normally countenance, or of groups targeting the wrong enemies, etc!

These opposing groups, and the current state of play between them, should be part of your campaign briefing materials, the springboards from which the players generate their character backgrounds.

But it is always possible to reverse-engineer the information from existing character backgrounds. In fact, I would go further than that, and state that the GM should re-engineer his campaign background after the PCs have been generated, just to make sure that everything fits.

One of the best techniques is to treat the character background generation process as a series of mini one-on-one roleplaying sessions. Take an hour with each player to work through the past history of the character and how the different factions and campaign history have influenced them. This can either be done in place of a day’s play, or can be done away from the table.

Generate rumours

There’s usually a vast gulf between what is actually happening and what the general public thinks is happening. Generate rumours that describe the latter, and pre-load your characters with them. These are usually the mere tip of the iceberg in comparison to the real story, but these breadcrumbs are starting points. Some of these will never become relevant to the campaign, some should be out-and-out wrong, and some should hold a nugget of truth. Some should directly conflict with the rumours given to other players. Some should be wildly improbable. It’s up to the character to assess how credible he finds them.

To generate these, I usually start with a true statement describing an event and break it into short, declarative sentences. I then wash each sentence through a “Chinese Whispers” process – rephrasing and restating the message, changing factual information slightly, occasionally inverting or distorting the meaning. I’ll generally roll a d6+2 for the number of times each sentence should be ‘processed’ – what comes out is a bunch of rumours describing the incident.

Most of these changes will be in the direction of heightened drama, even of melodrama. Exaggeration, hyperbole, and rumours go hand in hand! Sometimes I will like the ‘amped up’ version so much that I’ll make it the literal truth and start the process over!

Generate propaganda

Every power bloc will generate propaganda of some kind. This might be to play up or play down their activities and motivations, or to assign blame for something to their enemies (however big a stretch it is). Each PC, by virtue of who they are and who they have had contact with, will be ‘exposed’ to this propaganda, which can also be stated in the form of rumours; their relationship with the source will dictate the level of credibility.

If a rumour will not be believed by the character because their opinion is coloured by their existing relationship with the source, that rumour should be rephrased as a ‘conspiracy theory’ element before it is given to the character; instead of a rumour that “X did Y,” tell the character that “The [prejudice target] is trying to make people think that X did Y,” where the ‘prejudice target’ is someone that the character already thinks the worst of. I will often run the results through the “Chinese Whispers” process a couple of times before doing so. Exaggeration and Hyperbole, always!

This is usually impossible to decide until the character histories are known, and hence what rumoured actions the character will find credible. And the resulting rumours should be interspersed with those from the previous section, more or less at random, so that players can’t block-assign credibility assessments.

Determine next actions

Once you know who the power blocs are, and how they operate, you can also decide what each faction’s next step is going to be, even if the answer is “lie low until the heat dies down”. Have any recent events in the campaign background presented an opportunity that is too good to resist? Have a faction take action accordingly. Have any recent events left a faction vulnerable? Alliances may be formed or broken, leopards may change their spots, etc. Every faction should always be doing something to bring advantage to themselves and disadvantage (or discomfort) to their enemies – even if they are nominally on the same side!

Generate rumours of the results

You don’t have to decide on the outcome just yet – these are events that are taking place concurrently with the PCs adventures, and in which they may take a passing interest or even an active involvement. You should always scale these broad actions down to determine what the local events are that the PCs will see, first-hand, based on where they are and where they intend to go next.

The other thing that needs to be done is to note when these actions will become apparent to the faction’s opposition, and how long they will actually take to complete.

Generate rumours of impending enemy responses

Every action has an unequal and opposing reaction, to misstate one of the most famous laws of physics. This misstatement is literally true when it comes to the maneuverings of factions – their enemies will always take an opposing position, i.e. will react in some manner, and the strength of this reaction will always be greater or less than the original action, depending on the level of threat perceived in the original action. The smarter the heads of each faction, the more appropriate their response will be. Some of these reactions will be covert, some will be overt, and many will have a secondary reaction designed to act as a ‘cover story’ or misinformation to distract the enemy while the real move is being made.

Of course, no reaction can take place until the target faction knows there is something to react to, and by the time an action is complete, it’s usually too late to undo the effects. The numbers assigned to these two time-frames in the previous section dictate the window of opportunity for a counter-operation by the target faction, and the later into that window a reaction comes, the more likely it is that it will need to be some overt response.

Determine actual enemy responses

It’s my preference to come up with half-a-dozen possible reactions in the form of rumours, ranging from the improbable to the near-certain, wash these through the “Chinese Whispers” technique a few times, then pick the actual reaction that will take place.

None of these reactions will take place in a vacuum – all the moves being made by other factions, against other targets, will change the environment just a little. Other, presently uninvolved, factions may also get involved because they perceive an opportunity or a threat.

Each reaction then becomes a new action in this never-ending game of chess.

Update ‘The Big Picture’ regularly

These ‘boxing matches’ may be economic, or political, or social, or related to intelligence-gathering, or propagandist, in nature. A major side-benefit is that the campaign background is never static; it is always evolving, and introducing new plotlines that the PCs can get involved in. This obviates any need for plot trains at the same time as it brings the world to life for the players.

The downside is that as each action matures, the campaign background needs to be updated. For this reason, I like to stagger the outcomes of actions, making some brief and opportunist, and others subtle, preplanned, and long-term. The nature of the faction clearly needs to be a factor in these determinations. As a rule of thumb, I like no more than two factions to have acted or reacted in any given post-session update; this keeps the campaign admin at a manageable level.

Another advantage of this approach is that the material that can be given to new players, or new characters, is always pretty much ready-to-go. And if you take a holiday it’s relatively easy to get back into the swing of things by reading through your updated background.

Listen to your players’s ideas

Your players will put 2+2 together and come out with 7 on a regular basis. Sometimes, their ideas will be better than yours; sometimes, you will have a grand plan that their ideas don’t fit. You should always take the player’s theories and consider them carefully to decide whether or not they are better than your own. And if they are, you smile, give them a metaphoric pat on the back, and never admit the truth! They will not only think of themselves as brilliant (and pride goeth before a fall), but because you agree with them, they will see you as brilliantly Machiavellian to boot.

Make an INT check for the speaker

One approach is to secretly make an INT roll for the character whose player announces the theory. Succeed, and their theory is correct; fail and they’ve got it wrong. All game systems have some sort of mechanism that addresses this need, or can be adapted to it. The result is that no matter how brilliant the player might be, it’s the character whose brilliance or lack thereof that is reflected in the campaign events. Of course, if you really like the idea, you can ignore or even fudge this roll!

Even if there are some plot holes or logic errors to be filled in, this can still be a powerful weapon in making the campaign credible.

Red Herrings

These should be part and parcel of any set of rumours. In fact, many of the results of the steps described above won’t be characterised as anything else by most DMs. The alternative is for the rumours to give a roadmap to the overall plot, once a few side-roads created by mistakes in logic (or simple misjudgements by the players) are eliminated. Nothing kills game-play quicker than being able to predict with certainty every step of the rest of the campaign; it kills the suspense.

I have seen suggestions that red herrings should outweigh true rumours by 5-to-1 or more. I don’t agree with that; much of this quota will be met by rumours that are related to the truth, but heavily distorted, and I don’t consider those to be true “red herrings” as they still advance the plot.

A genuine Red Herring is a deliberately-false rumour that is inserted into the mix for the express purposes of deception. The problem is that if there are too many of these, players will never be able to sort the wheat from the chaff and, as you put it, “get their heads around the plot”. Worse still, the players may come to feel that the DM is deliberately trying to deceive them. That’s why the majority of false rumours are not red herrings per se, just propaganda from one faction or another; that then becomes something that illuminates the nature of that faction, and something that is “their” fault, not something that is “you vs the players”.

I think that a ratio of one-in-five or even one-in-ten is about right, representing people who invent wild stories out of thin air for the pleasure of hearing themselves speak (and to make themselves, however briefly, the centre of attention).

Pink Salmon

I am especially fond of rumours that can be easily dismissed as Red Herrings – but aren’t. A few pieces of “Pink Salmon” – to extend the metaphore – makes everything more credible. It’s always possible that some of the wild stories invented by these local wits and spread far and wide by the gossip of passing travellers actually hit the nail on the head.

Be selective, though; you don’t want to introduce a “the more improbable it sounds, the more likely it is to be true” dynamic into your rumours, because that also kills the mystery and suspense of the campaign. As a rule of thumb, 1-in-5 or 1-in-10 “Red Herrings” should actually be Pink Salmon.

White Salmon

PT Barnum could sell just about anything. The story is that he once came into possession of a truckload of grey salmon, which are neither especially popular nor tasty. He relabelled them “White Salmon,” (there’s no such thing) “Guaranteed never to have been pink”. And sold the lot at premium prices.

Perception and salesmanship counts for a lot. Rumours are no good if you don’t sell them to the players through roleplay. Any tavern scene should involve a chat with the local gossip to get the latest unofficial news and a sense of local affairs. These should be two-way conversations, in which the players get to pass on rumours they’ve heard as well as receive new ones. In essence, you have to label your rumours as “White Salmon” and sell them to the players.

It might seem that it’s enough to convince the characters of the validity of rumour #112, but it’s not. The players may have their characters act as though deceived, but it’s not very satisfying when the players know better. So make no mistake, this is an essential application of metagaming that can have a major influence on the entertainment value of your game – you might be pitching your rumours at the characters, but it’s the players you have to convince.

Maintain an atmosphere of uncertainty

This is so important that, even though I’ve mentioned the maintenance of suspense a couple of times, it bears repeating again. Some GMs suggest that every time the players figure out what is really going on, the universe should be torn down and replaced with something even stranger (shades of The Hitch-hiker’s Guide To The Galaxy!).

Personally, I wouldn’t go that far; you risk a complete loss of credibility and of the players losing all confidence in their ability to actively decide their own fates. In effect, you can convince the players they are on a plot train even when they aren’t, if you go too far – I speak from personal experience.

This requires a judgement call or two on the part of the GM. Will the player’s knowledge of the truth impact their immediate activities? Then they’ve got it right, and should be congratulated. Will their knowledge of the truth have a negative impact on the entertainment value of future scenarios, or will it enhance it by offering a glimpse behind the curtains? If the first, then they’ve got it wrong and the GM needs to introduce a new explanation for what’s happened; if the second, then they have it right.

If both these judgement calls leave the question in a gray area in between, then the rule of thumb I use is that the players are probably right, but something prevents them confirming it – for now. It becomes a deeply-held suspicion of the characters, nothing more.

It is also important to note that juicy rumours don’t stop just because the PCs have proved or disproved them, and resolved the source upon which they were based; rumours should linger, and occasionally raise doubts about whether or not the problem really WAS resolved!

Imminence brings revelation and certainty

The more involved in any given faction-fight the characters get, the more reliable should be the information they receive. The closer to fruition a faction’s plan becomes, the more blatantly obvious it should become – though this is always a relative value.

Consider the land invasion of the allies in World War II: at first, it was just speculation when and where it would occur; then it became inevitable that sooner or later it would occur, but where and when were still no more than guesswork; then preparations for doing so got underway and deception and misdirection were employed to make sure that the enemy didn’t know where and when it would take place; and then finally it actually happened, at which point it quickly became certain where and when it had taken place.

Example of the “Chinese rumours” technique:

1. Bishop Luabird spent $100 on lady’s underwear.

2. A Bishop in good standing spent $100 on exotic lingerie.

3. A disreputable bishop in the south regularly buys exotic lingerie.

4. A disreputable bishop in the south wears exotic lingerie.

5. A disreputable bishop in the south wears the skin of a devil as underclothes.

6. A bishop in the west wears the skin of a devil.

7. A disreputable bishop in the northeast is controlled by the skin of a devil that he wears under his clothes.

Now feed the last three to the PCs! Notice that even if the original rumour is true, there is no explanation of why the Bishop needed the underclothes!

Summary:

The key to running a completely character-driven campaign is to work out what the opposition is doing, generate rumours accordingly (including exaggerations and red herrings), and then let the players interpret these as they will. Rumours will often persist long after the cause of the rumour has been resolved – which should leave your PCs always wondering whether or not they have really solved “The Riddle Of The Headless Horse Thief” or whatever. Then let the players decide what their characters deem interesting enough, or important enough, or even simply credible enough, to get involved in. And when they make that decision, the first thing they are going to have to do is find out what’s really going on – which means roleplay.

Johnn’s answer:

Great process, Mike! I especially like the rumour washing. That’s a nifty little engine GMs should master because they can get so much value from constant use of it.

I don’t have anything to add to Mike’s process. So instead, I’ve distilled this post into a series of steps and created a short PDF game master checklist everyone can download and use in conjunction with this post.

![]() Grab the checklist. Then use it along with referencing this post to help guide you along.

Grab the checklist. Then use it along with referencing this post to help guide you along.

Ask The GMs is a service being offered by Campaign Mastery. More info >

October 12th, 2009 at 5:46 pm

Excellent post. I especially like the Chinese rumours technique.

.-= John L. Williams´s last blog ..Have your PC’s suffered enough? =-.

October 12th, 2009 at 6:40 pm

First of all, I’d like to thank Mike for his breakdown of the situation. I have one word to say: WOW. Sorry this is going to be so lengthy, but I am going to address some of the things you said.

In addition to having multiple storylines, I also need to say that just because the players are investigating one (or maybe a couple if they get the right rumors) rumors at once, as time goes on, whatever ones they are not investigating, the consequences of not dealing with that plot line becomes more and more severe. For instance, if I have 3 plot lines going on at once, for convenience labeled “A, B, C,” “J, K, L” and “X, Y, Z” respectively. They find out about A, which leads to B, which culminates in C and at the same time X -> Y -> Z but they don’t have time to look into J -> K -> L – the final disastrous product might be present where they have no choice but to address it. But is that fair to the players who spent their time elsewhere?

You wrote:

[Characters need] back stories that motivate them to be interested. A little personal stake in the outcome makes a big difference… [and] to ensure that much of the character backgrounds are open-ended, unresolved, or otherwise unexplained.

When I read a background, or plan a plot point I go by a motto “NEVER is everything EXACTLY as it seems.” Cogs within cogs, and shadows within shadows – Just when they think they have the whole story, some other piece of information is found or needed to make everything fit.

You wrote:

Every significant power bloc should have a defined opposing power bloc, and the drive of the campaign should emerge from the tension, the move-and-countermove, between these groups. And don’t neglect the potential of groups that are being blackmailed into activities they would not normally countenance, or of groups targeting the wrong enemies, etc!

I try not to have it as a “this side against that” I try to have 3 or more sides to an issue. In D&D there are 9 alignments which can be roughly divided as “good, neutrality, evil” and “law, neutrality, chaos” (though I never divide things up that neatly)

You wrote:

There’s usually a vast gulf between what is actually happening and what the general public thinks is happening. Generate rumours that describe the latter, and pre-load your characters with them. These are usually the mere tip of the iceberg in comparison to the real story, but these breadcrumbs are starting points. Generate rumors that describe the latter, and pre-load your characters with them. These are usually the mere tip of the iceberg in comparison to the real story, but these breadcrumbs are starting points.

Maybe that’s the core of some of the problem(s) I’ve been having. I’ve told way TOO much of what actually IS going on vs. what people think is going on. But what’s wrong with the way I did things? Everyone can have their own character stories, their own reason (and sometimes *no* particular reason) to be in town – in essence side stories to the main plotlines, and each of the side plots add depth to the overall storyline, and may or may not be (ultimately) relevant to the overall plot.

You wrote:

Each PC, by virtue of who they are and who they have had contact with, will be ‘exposed’ to this propaganda, which can also be stated in the form of rumours; their relationship with the source will dictate the level of credibility.

Sometimes the ‘truth’ of the situation is far uglier than anything that can be (reasonably) believed, even if it IS the truth. (Briefly), an example of this was when a character I had introduced in a one on one game showed up stark raving mad. She knew a good portion of what was going on, but no one would believe her (in fact she was so mad the players didn’t even ATTEMPT to hear her out)

You wrote:

One of the best techniques is to treat the character background generation process as a series of mini one-on-one roleplaying sessions.

I’ve done this, but kinda in reverse. I gave the rumors out and they did a RP session to find out more. One person’s RP gave them a LOT more information than I had originally planned on giving out, but the rolls were in their favor (and with rolls THAT good, I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to show a bit more of the picture)

You wrote:

You don’t have to decide on the outcome just yet – these are events that are taking place concurrently with the PCs adventures, and in which they may take a passing interest or even an active involvement.

I was trying to build a game around their active involvement, making the rumors the ONLY things the PCs actively were involved in. Maybe that’s another problem in my approach.

You wrote:

Every faction should always be doing something to bring advantage to themselves and disadvantage (or discomfort) to their enemies – even if they are nominally on the same side!

What about factions so new that they seem really to have no sides, save their own? No one actively opposes them per se, but no one that takes an interest in their activities either.

You wrote:

[Regarding plot/ actions some will be] brief and opportunist others subtle, preplanned, and long-term.

Is there such a thing in a campaign where something is simply too big to be stopped? Even if they “nip it in the bud” there, similar [possibly even unrelated] events happening elsewhere bring it about anyways – tho maybe not in the same way I had originally planned? Or is that wholesale cheating on the behalf of the DM?

You wrote:

Rumours are no good if you don’t sell them to the players through roleplay. Any tavern scene should involve a chat with the local gossip to get the latest unofficial news and a sense of local affairs.

I completely agree. Though if I had to give EVERY rumor out via bar conversation that would be tiresome. Some of the “essence” of the rumors I have them experiencing directly. Some of them I had them start out with (having them roll for which rumors they got)

You wrote:

Your players will put 2+2 together and come out with 7 on a regular basis.

That’s happened to me and they were putting together things that had nothing to do with each other (and couldn’t, in fact because of their disparity of locations)

You wrote:

Will the player’s knowledge of the truth impact their immediate activities? Then they’ve got it right, and should be congratulated.

Sometimes when they get “7” instead of “4” their actions are crazy, and they go about searching for things that don’t exist. When that happened I FELT like telling them “ok, this is how these things are connected, this other had nothing to do with it!”

—

You mention updating the big picture. I hadn’t thought of that before other than having things continuing to go regardless of whether the PCs investigated or not.

Oh, a final question: for the sake of completeness do you want to see the rumors I’m starting with?

October 12th, 2009 at 9:55 pm

@ John: thanks! I’ve always found the technique useful.

@ James: Glad you found the answers thought-provoking and hopefully useful.

Okay, this presupposes that the PCs are the only people in the world that are able to deal with any given situation – that unless they intervene, a plot will run through to completion. In reality, there would be others opposing any given group trying to achieve something, and while the solutions produced by these third parties might not work as well, or might have widespread consequences and collatoral damage that the PCs might have been able to avoid, most of the time the status quo will be more-or-less maintained. The PCs are a deciding vote, a trump card, but they can only be in a limited number of places at the same time.

It’s the collatoral impact that changes the world, usually. EG Hitler comes to power, launches a plan for the conquest of Europe. Stop these plans early enough and there’s minimal impact. Wait too long – say, until you have the clear moral authority to do so – and you have World War II. At the end of which, Germany is defeated, and the status quo restored. Aside from all the fallout and collatoral damage done along the way. Is a code of honour worth all the lives lost? Would you be damned for all eternity to stop it from happening? Hindsight is always better than 20/20, because you always know more about what was really going on after the fact.

Absolutely, the closer to completion an operation is, the bigger the problem is when someone finally gets around to it, and the more widespread the consequences and fallout will be. Part of what I tried to present is a means of determining who (other than the PCs) will solve a problem that they didn’t tackle in time, and what the consequences will be of the third-party solution.

Is that fair to the players who have spent their time elsewhere? If the PCs are trying to tackle the problem, absolutely not. Once the PCs take an active hand, the players should be the authors of the solution. Even then, there will be others who will make countermoves without consulting the PCs, and who will complicate the situation as a result; but the ultimate solution should belong to the players. If the PCs are dealing with something else? Then, unless you can justify slowing the progress of the plan because of third-party interferance until the PCs get around to the problem, then it’s absolutely fair, because it’s a background event. The fallout and consequences of the solution will pose a new problem for the PCs!

For example, the Players in my One Faith Campaign have just discovered that a problem that seemed to be of extremely low urgency and relative importance is the common factor that has made all the other problems that they face so difficult and urgent, and if they had tackled this seemingly minor issue first, they would have taken a lot of the sting out of the other end-of-the-world-as-we-know-it issues. Whatever they have tackled, they have solved; but because all the problems they hadn’t dealt with yet kept getting worse, the overall situation was deteriorating.

Omniscience, even in part – which is what too much right information is – makes those who have the information more likely to make the right choices of action, increasing the effectiveness of the PCs targetted attempts at a solution, and avoiding them wasting time on blind alleys.

It also subtracts a little from the realism of the campaign, because you don’t have different sides throwing propaganda out (and unrelated third parties blaming other unrelated third parties).

But that’s the only only problem with giving too much right information. Under the circumstances you describe when talking about your initial play session(s), I would have done exactly what you’ve done. And immediatly started developing new plots to keep the PCs busy when they are finished dealing with what I would have thought they would have spent the whole campaign dealing with!

If it’s a new faction, then it has a goal and an agenda; there will be something that they want to change and hence their (unknowning) opposition is whoever is benefitting from the status quo, or there will be something they want to preserve as is, in which case their opposition will be anyone who threatens to change that aspect of the status quo. For a while, they may have no organised faction opposing them, or they may have a number of pre-existing factions opposing them without knowing they exist. The more subtle the tactics adopted by the new faction, the longer they will go without an active opposition targetting them, and the more events will seem to “spontaniously” go the way they want them too – but the more they change things, or prevent change (whichever they happen to want), the more passionate those individuals who want the opposite to happen will become, and eventually, they will spontaniously form an opposing faction. They may not know who they are opposing, or why events are occurring, and they almost certainly won’t see the big picture – but by reacting to the events they don’t like, and trying to alter the outcomes for which the first faction were responsible, they place themselves in opposition. And if they don’t know who they are opposing, conspiracy theories and intelligence gathering will be the priorities.

Again, to use WWII as an example, it can be argued that Hitler’s biggest mistake was allying with Japan; if he had not done that, then the US would have made dealing with Japan a higher priority than getting involved in the European situation, giving him a far better chance of achieving his goals. By the time the US turns their attention back to Europe, they are not only weakened, but face a far more entrenched fait accompli. They might well have baulked…

A faction – even a new one – doesn’t exist unless it’s trying to achieve something. And that agenda automatically creates the opposing force.

There are so many ramifications to this question that I can’t begin to do it justice here – so I’ll give a fairly unsatisfactory response and mark it down as the subject of a future article here at CM.

The short answer is yes, it can be reasonable to have something so big coming that even if the PCs stop one cause of a given change, other causes can produce the same result. But unless the PCs know that other forces are pushing towards the same result, it still feels like a DM’s plot train. So the only time that I would do this (even though it’s unrealistic) is if their victory gave them the necessary information to stop whatever is happening at the 13th hour in one last, desperate, act…

Exactly right. What should happen in this situation is that they buy into one situation, expecting it to solve two things, and find out that one had nothing to do with the other. It’s only when the “7” is a logical and rational answer that you should consider going with their solution and not what you had in mind.

While they might be interesting as campaign seeds for other people, I don’t think so. You never know when one of your players will come across this blog….

October 13th, 2009 at 12:35 pm

Yes, your advice was very thought provoking and useful THANK YOU!

October 13th, 2009 at 6:41 pm

You’re Welcome!

October 15th, 2009 at 7:12 am

That is some darm good info right there! I for one have always had a problem with giving away too much information too fast, though in my defense all but one person in my gaming group is of the “kick in the door and beat whatever is moving untill it STOPS moving” kind of players, so usually I don’t bother… However, excuses aside, I obviously don’t have much experience when it comes to mysteries and propaganda that are more complex than your average action movie plot, so this post was highly useful to me.

October 15th, 2009 at 8:20 am

Glad it was of help to someone else. I get a lot of inspiration from lots of sources, among which are:

(multiple) anime(s)

my favorite authors

Soaps

real life

The one thing about real life (and I’ve found it to be true) is that “life is stranger than fiction.” Fiction has to make some sort of sense — real life doesn’t!

Maybe it’s the author in me that doesn’t like trying to “fool” players with rumors that aren’t true, but whodunnits are filled with authorial slight of hand, innuendo, and outright deception as far as (even if the people reading it know exactly what’s going on) the people investigaing know.

October 15th, 2009 at 8:56 am

Hey, James, that’s why we operate this service. We aim not only to help the person asking the questions, but – by extension and example and insight and inspiration – other GMs who might find the answers valuable!

October 15th, 2009 at 11:48 am

I was half afraid that the question was so… esoteric that no one else would be able to benefit from it, that’s why I’m glad it helped at least one other person

October 22nd, 2009 at 1:22 pm

This is beautiful, poetic even. I feel illuminated and think I can be a much better GM now that I can consciously put this in to practice. I always have open ended campaigns with multiple plots my players can follow or not with an evolving background, but it has mainly been based on whims with no system behind it.

It happens way to often that I get lost in my story and loose my players in it while we all flounder trying to find the top from the bottom.

Thanks for this great foundation I can now use to refer back to when I loose my trail.

October 22nd, 2009 at 4:09 pm

Happy to have been of service, Guidance! I would suggest that rather than wait until you’re lost in the tall grass, employing a periodic review might be a more helpful approach. It’s astonishing how helpful it can be to do a private listing of “what’s going on and who’s doing what to whom” every now and then to avoid getting lost along the way.